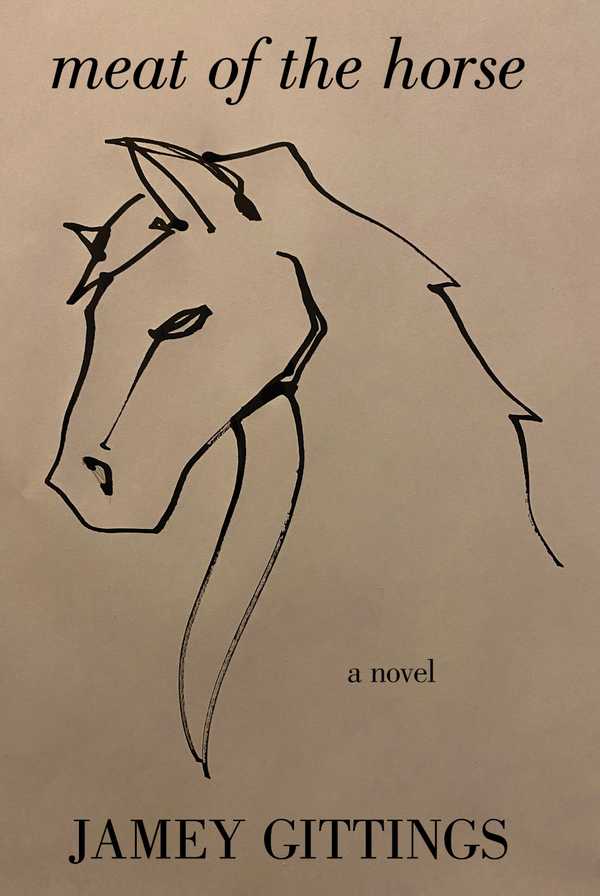

A Meal Called Horse

It started something like this. I wasn’t there; well, not exactly, but it happened very much like this: Dr. Gerard Lavoisier, chief thoracic surgeon, head administrator and lecturer on anatomy at Paris’s prestigious Saint Bridgid’s teaching hospital, was pleased. He had arrived early at the Hotel Nigresko, which gave him time to admire himself in the gold-flecked mirror of the opulent men’s room off the lobby, just outside the restaurant. And he was quite satisfied with the reflection. He was losing a little hair, it was true, but the loss revealed a broad forehead, and the grey that shot, more and more, through the black only added distinction to his fifty-seven years. And, as he reflected, he had more than many men twenty years his junior. His stomach was flat, his posture erect; his overall physiognomy athletic. It was Friday night after a long week, and he was looking forward to the evening ahead. Yes, he would be more than up to this night’s task.

He had come to redeem a note. A note with a woman written with their eyes several weeks before. It was certainly not his first such note. For he was a man of prestige who could trace his ancestry to the famous chemist of the same name, and with this prestige came a certain level of privilege and power that he exercised with moderation, unlike many of his colleagues.

Veronique Broussard was a gifted surgeon in her own right, though with less experience than Lavoisier. Despite her youth, she had paid considerable dues working in war-torn African countries, each year in that theater being easily worth five or six at a teaching hospital. Had she not been the most impressive and qualified candidate for the position, he still would have engineered her hire, for she was quite beautiful, with eyes the size and color of an Okapi and the legs of a track star. He had let her know at her first interview that there were other qualified applicants, many of whom had their own champion on the faculty. It would be difficult, but as head of the hospital, he would do what he could. He had written the contract with an earnest stare and raised eyebrows, and she had signed it with a slow blink of her eyes. Additional interviews had notarized the contract, and tonight the note would be foreclosed. He had made reservations at his favorite table and booked a room at the hotel. Everything had been planned down to the menu and the wine, a Chateau Margaux 1927. If she had any doubts about him, the wine alone should banish them. So, it was with complete confidence that Dr. Gerard Lavoisier strode from the Hotel Nigresko men’s restroom toward the lobby to meet his Veronique.

She was there waiting, of course, since this night would be perfect. She wore a simple but elegant black spaghetti strap evening dress, and looked confident and at ease, her track star legs relaxed. “Bonsoir,” said Dr. Lavoisier.

“Bonsoir,” answered Dr. Broussard as she tilted her cheek upward toward his kiss. With his arm around her waist, he escorted her to the restaurant where they were installed with solicitude at Dr. Lavoisier’s table.

“I have taken the liberty to order for us so that the chef may prepare one of his most special creations, and have chosen a good wine,” said Dr. Lavoisier with understatement, as the waiter, on cue, advanced on them with the bottle.

It was here that the perfect evening first began to crumble. “Oh, I’m sorry, I do not drink alcohol. Perrier,” she said, smiling easily at the waiter, who poured a small amount of red fluid into Dr. Lavoisier’s wine glass and waited for the staring physician to give his approval.

Remembering himself, Gerard swirled the wine around his glass and swallowed. “Very nice,” he said, nodding as the waiter. Who filled his glass to slightly above a third and disappeared. Putting an end to the awkward silence, he returned almost immediately with a large bottle of Perrier and began to fill Dr. Broussard’s glass.

At that moment, there was the sound of dishes crashing on the floor; interrupted, the waiter stopped his pouring to look up, and Veronique took advantage of his pause to lift her partially filled glass. She sniffed it, swirled the clear bubbling liquid around the glass, took a dainty sip and smacked her lips. “Very nice,” she said, nodding in a parody of Gerard’s ritual a moment earlier. She put her glass down and giggled so loudly that nearby heads turned toward her. The waiter, despite years of training, ejected a slight chuckle that was quelled immediately by a fierce look from Professor Lavoisier. Veronique gave another giggle that terminated in a snort. “I’m sorry, I always wanted to do that in a place like this but never had the chance. Thank you,” she said.

“Quite all right,” said Gerard, his first words since “very nice”, in a voice that said clearly it was not.

“Tell me what delights you’ve planned for our dinner,” said Dr. Broussard, trying to enliven the conversation that was now about as animated as a tombstone.

“Ah,” said Lavoisier, “it is a special delicacy, one that I am sure will enchant you. It is called paardenrookvlees and is a particular specialty of the house chef.” He sipped his wine and smiled.

“Oh,” said Veronique, smiling, her Okapi eyes as wide as the entrance to the Chunnel, “I’ve never heard of it. What are its ingredients?”

“It is the marinated and sliced meat of the horse, quite difficult to get and prepare correctly, but when done right—it is magnificent.”

“Horsemeat?” said Veronique.

“Ah. Yes, the meat of the horse.”

“Goodness, do people really eat horses?” said Dr. Broussard. Gerard braced himself for another giggle, but none came. “I don’t think I could ever eat a horse. I used to ride quite a bit as a little girl at my father’s summerhouse outside of La Rochelle.” Dr. Lavoisier just stared.

“Actually, I’m a vegetarian,” continued Veronique. “I probably neglected to tell you that.”

“No. It did not come up,” said Lavoisier as the waiter set down the soup.

“Andre, there has been some confusion, Dr. Broussard is a vegetarian. We will have to make some alterations in our order. What have you for a vegetarian?” This last word could have substituted with leper.

“Little on the menu, sir, but we can make up a fine plate for the beautiful mademoiselle, and the soup is vichyssoise, thankfully only potato. Does the mademoiselle eat eggs and cheese?” asked Andree, reassured when she answered yes.

“French restaurants can be difficult for vegetarians,” said Veronique. “Not as difficult, however, as Africa. Even very poor people want to give you their best, and that’s inevitably meat. I was always dancing around offending people as I avoided whatever meat was in the food.”

They talked a little more about Africa, and a little about the hospital. Gerard was most comfortable talking about himself, but there weren’t the usual openings with Dr. Broussard. And both were thankful when the meal came.

Andre, true to his word, had arranged for a mosaic of all kinds of vegetables, fruits, cheeses, and breads that could have been mistaken for a stained-glass window from a distance. The horsemeat dish reminded Veronique of the operating table, composed of red meat in a brown sauce broken only by the orange of carrots and the green of parsley. Gerard held his bites out in front of him and gestured with his fork as he ate, intermittently hoisting his wine glass like a scepter, as if he were lecturing to an undergraduate class on the virtues of meat and alcohol. Dr. Broussard munched her vegetables with an unladylike gusto that Lavoisier found annoying. Her smile and conversation, not to mention her eyes and legs, he found delightful, feeling the night could still be salvaged.

She was talking of her experiences in the Sudan when she noticed Gerard’s head jerk forward. He placed his fingers in his mouth and extracted what appeared to be a small bone.

“There are no bones in the meat of the horse. This is simply unacceptable,” he said examining what he held in his hand. Then upon looking closer, his culinary outrage turned to the scrutiny of an anatomy professor. “What is this?” he continued, turning the bone over in his fingers. “I don’t think this is any part of a horse.” Dr. Broussard, now interested, leaned over her plate to get a better look. The fragment consisted of two straight pieces separated in the middle by a joint.

“It looks human,” said Lavoisier.

“Yes,” said Dr. Broussard. “A part of a digit, finger, maybe a toe, but definitely human.”

Gerard held the bone fragment out between them, and they both looked at it, then at each other with puzzled faces. Veronique cast her eyes down to the table and was the first to see it. There, resting serenely amongst the pieces of horseflesh, nestled in the brown sauce was a nearly intact, though thoroughly marinated, human thumb. “I believe this particular horse had taken the major evolutionary step toward opposable digits,” said Veronique, drawing Dr. Lavoisier’s attention to the thumb by pointing at it with her fork. Gerard looked down at what had served as his dinner. Dr. Broussard gave another reflexive snort and giggle as she gazed into the unamused, yet curious, face of her colleague.

The scene at the table would likely have been quite different with diners other than two experienced surgeons. Dr. Lavoisier’s dinner plate quickly transformed into a dissecting tray, as Dr. Broussard probed the object of interest and its immediate environment with her fork. “It is completely intact, severed cleanly just below the knuckle.” Veronique spoke as a veteran of thousands of severed limbs, digits, ears, noses, and other various body parts. “It looks positively mummified. Look, the fingerprint is clearly visible. This marinade is good stuff.” Lavoisier just stared. The evening was in ruins, his perfect batting average in grave danger.

Veronique was deep into the scientific mode, as she reached over to take the original fragment from Gerard, who still held it in his hand. She turned it over in her fingers and examined it from all angles. “Clearly a finger, probably the index,” Veronique continued forensically. “There’s very little flesh on it. You don’t suppose you swa…” Veronique stopped just short of calling her dinner partner a cannibal and successfully suppressed another giggle, though not the attendant snort.

Lavoisier blanched, then recovered his administrative demeanor. “We need to call the police,” he said.

Or we could take it to the station in a doggie bag, thought Veronique, thoroughly enjoying the evening she had been dreading for weeks. “Yes,” however, was what she said.

“Andre,” called Dr. Lavoisier. “We need to call the police.”

“I hope the dinner was not so bad as that, Doctor,” said Andre.

“Shall we say it was not quite the delicacy I had ordered,” said Gerard to the confused waiter. Veronique shot Gerard an approving smile.

“Perhaps, Andre,” said Dr. Broussard, “it is an even greater delicacy when it includes not only the meat of the horse but also the rider.” Bursting now into uncontrollable laughter, she was immediately sorry as Andre, who was not a thoracic surgeon, or a surgeon of any kind, glimpsed the thumb and bone fragment resting together in a background of brown sauce garnished with julienne carrots. His reaction was typical for those not desensitized to severed pieces of human anatomy, as he steadied himself on the table, put his hand over his mouth, and fled the room.

The police came, interviewed the two surgeons, bagged the evidence, and confiscated the remainder of the restaurant’s horsemeat along with Dr. Broussard’s refused entree, then went away. The policeman in command would not allow any further examination by either doctor, despite Veronique’s pleading, although he did make a note of her suggestion that the thumb should yield an intact and readable fingerprint. Had the evening been a small city, Dr. Gerard Lavoisier, MD, professor of anatomy and chief hospital administrator, would have been standing thigh-deep in rubble, yet he made one last valiant attempt as they stood in the Hotel Nigresko lobby.

“I did book a room at the hotel for tonight,” he said, looking directly into those Okapi eyes and raising his eyebrows slightly.

“Oh, thank you for one of the most enjoyable evenings I’ve had in a very long time,” said Dr. Veronique Broussard. “But I have to go home to my daughter and liberate the babysitter.”

“You did not tell me you were married.”

“I’m not,” answered Veronique. “I have a nine-year old daughter that I adopted five years ago in North Africa. She’s quite delightful, though a bit of a handful for my sitter.”

Reading the clear frustration on Dr. Lavoisier’s face and having been in similar situations all over the world throughout her career, she bought some retaliation insurance.

“Oh, and Gerard, our secret about that index finger thing is safe from our colleagues. They can be so, shall we say, adolescent sometimes. Au revoir.” She smiled easily, and with a toss of her head disappeared through the revolving main entry.

How do I know all of this without having actually been there, you ask? Come along and see.